CO-DEFINING TRANSITION INDICATORS

How Shared Values Advance Holistic Urban Transitions

By Rebecca Wessinghage, Transition Concepts Officer, ICLEI – Local Governments for Sustainability

At present, the mainstream approach to differentiate developed or industrialized and developing societies uses a linear ranking of economic productivity and gross domestic product (GDP).[1] The underlying assumption is that a high GDP would automatically increase citizen well-being. Yet, the consequences of highly industrialized economies – the depletion of natural resources, environmental pollution and climate change as well as social inequality – have become undeniably apparent over recent decades. These rising challenges are particularly strong in industrial legacy cities, whose spatial and economic growth was almost entirely driven by industrial development.

In the industrial boom cities of the German Ruhr Area and the U.S. “Rust Belt”, local economies became dependent on single sectors, which led to low resilience to changing economic trends. When key sectors started to decline, inequality challenges were amplified by widespread job loss and infrastructure disinvestment that primarily impacted the large workers’ populations in these cities. Looking back, economic prosperity was not protecting residents and social systems when facing a degrowth period. The high GDP in these cities had failed to create resilient and sustainable urban systems.

To be able to identify non-GDP focused transition pathways towards healthy, green and resilient societies, international and local experts joined the International Conference on Transition City in Seoul, South Korea, from 26-27 September 2019. Answering to the pressing realities of climate change, participants explored the potential of holistic urban development strategies that are based on transparent, collective indicators that reach beyond economic value and support core societal values such as quality of life, happiness, ecology and a healthy environment. Invited by the city of Seoul, The Urban Transitions Alliance cities of Pittsburgh and Essen had the chance to exchange with local government peers, researchers, and civil society representatives from around the world and showcase how their transition experiences have led to holistic and inclusive city strategies.

Throughout the conversations, three key steps emerged to accelerate systemic and lasting change:

- Firstly, transparent, data-driven assessments and participatory processes lay the groundwork for shared transition targets and clear criteria for monitoring and evaluation.

- Secondly, a thriving civil society and a diverse grassroots culture ensure that key challenges are addressed through a variety of perspective and approaches.

- Thirdly, strengthening education to mainstream sustainability thinking enables residents to participate in both the agenda-setting process as well as the development of locally specific solutions.

Examples from the host city of Seoul as well as from industrial legacy cities Essen and Pittsburgh illustrate how these pathways contribute to sustainable and equitable urban environments.

CREATING A SHARED VISION FOR THE CITY OF SEOUL

Although economically thriving, the city of Seoul faces major challenges concerning air pollution, social inequality and low life satisfaction especially amongst the younger generation. Past urban masterplans have largely failed to address major social and environmental issues in a systemic way. When an assessment of urban planning practices indicated a lack of inter-departmental cooperation and citizen participation, the city democratized the process used to develop the 2030 Seoul plan. Usually limited to spatial and physical elements, the scope was broadened to include quality of life related aspects like welfare, education and culture and invited all city departments to collaborate. From agenda-setting to implementation, citizen committees were actively included. A separate youth group was created to ensure that the views and needs of the future generation were acknowledged.

As a very first step, a shared vision of “A Friendly City Based on Mutual Communication & Care” was established. This vision guided further planning on value-based topics such as diversity, cooperation and innovation. In addition, the spatial structure of Seoul was revised to encourage more balanced development. A centralized structure with a single Central Business District gave way to a real-life concept with 3 city centers, 7 area centers and 12 regional centers, allowing for different development patterns based on regional specificities.

During the International Conference of Transition City, Seoul Mayor Park Won-soon emphasized the urgent need for action and introduced indicators for an inclusive transition.

Since the development of the 2030 plan, Seoul has continued to embrace an even more comprehensive approach to their urban transition process. The City has aligned its development strategy with the UN Sustainable Development Goals. This has led to the definition of ten social indicators and eight areas for happiness indicators, including satisfaction, housing conditions and social relationships. In parallel to new planning practices, Seoul Innovation Park has been established as a laboratory for social innovation and real-life solutions. Formerly a medical center, the innovation park features office spaces for around 200 non-profit organizations, meeting and workshop facilities for public use as well as parks and space for agricultural projects. Side by side, high-tech solutions are exchanged through a global innovation network, while other projects are promoting simple and localized lifestyles. Examples include a zero energy café and the adaptation of traditional farming methods to modern societal needs.

TWELVE INDICATORS LEADING ESSEN INTO A GREEN DECADE

18,500 visitors celebrating at the “Green up! Altendorf” district festival in the north of Essen.

Since Essen’s last coal mine closed in 1986, the city has presented itself as model for structural change. Initiatives include re-naturalizing polluted rivers, increasing green spaces and repurposing industrial infrastructures like factory buildings and railway tracks. Across transition programs, a great effort was made to conserve the city’s heritage and shape a shared identity that acknowledges its industrial legacy while leading into a sustainable future. In recognition of the fundamental transition from a coal and steel center to a green city, Essen has been awarded the title of European Green Capital 2017.

The main driver of this process is the commitment from the city to improve the quality of life of citizens. To achieve this, Essen developed twelve key indicators as part of its Green Capital strategy. These indicators helped to evaluate the current transition achievements against former conditions and set clear targets for the future. The indicator set focused on climate change mitigation and adaptation as a key priority and defined holistic sustainable development objectives covering land use and water management, nature and biodiversity, eco innovation and employment, and energy performance. City-wide implementation is ensured by integrated environmental management processes established within the city administration and through municipal affiliated companies. As Essen has consolidated the Green Capital efforts into a “Green Decade”, the twelve transition indicators have been reinforced by the city council as the core of Essen’s climate protection strategy.

CORE VALUES TO ACT ON EQUITY AND RESILIENCE TARGETS IN PITTSBURGH

For the former steel city of Pittsburgh, a key learning from its industrial transition has been to future-proof its economic, environmental and social systems. Based on a citywide participatory resilience assessment, Pittsburgh has developed a “OnePGH” resilience strategy that focuses on four key values: People, Place, Planet and Performance. These 4 Ps provide the foundation for holistic urban planning and support cooperation across departments and city stakeholders. For each of these values, sector-specific objectives have been developed such as housing, health and food (People), transportation, recapitalizes infrastructure and vacant land (Place), water, local renewable energy and resource efficiency (Planet) as well as entrepreneurship and civic engagement (Performance).

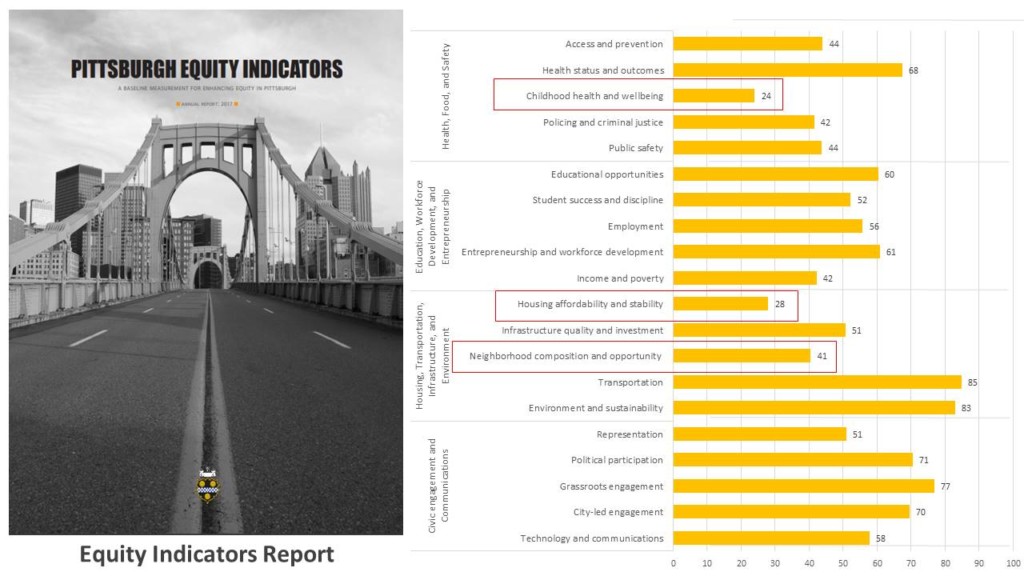

A cross-cutting transition challenge in Pittsburgh has been inequality among communities. To improve opportunities for all, 80 indicators have been established to assess equality in different sectors. In the subsequent years of 2017 and 2018, the status of these indicators has been evaluated to inform the city’s investment decisions and measure progress. As a result, childhood health and well-being, housing affordability and stability, and also neighborhood composition and opportunity have been identified as priority issues. Furthermore, a comprehensive and collaborative city assessment has been undertaken, the outcomes informing the Pittsburgh Investment Prospectus. To act on these findings, a local implementation fund is currently initiated as a third party mechanism to leverage and direct different funding streams.

To improve opportunities for all, Pittsburgh has developed equity indicators to assess equality in different sectors.

A next step for Pittsburgh is the alignment of the OnePGH strategy and local Investment Prospectus with the global Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Both Seoul and Pittsburgh have been incorporating the SDGs to support cross-sectoral collaboration and peer-to-peer exchange. Setting holistic values and indicators, the SDGs provide a global framework to identify societal challenges and guide transition programs towards more resilient and inclusive cities.

[1] UNIDO (2019): How does UNIDO group countries by stage of development? Retrieved from: https://stat.unido.org/content/learning-center/how-unido-groups-the-countries-by-stage-of-development%253f (03.12.2019).